![]()

[ Available in Spanish: " Iconografías Enmendadas " ]

Click on an image to see the full-size version !!

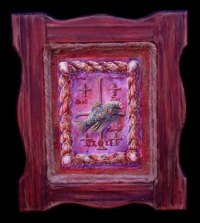

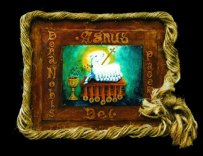

"Amended Iconographies" is a series of paintings, drawings, etchings, silkscreens, woodcuts, and assemblages which was begun in 1996 and continues today. It sprang from my search for personal faith and a subsequent exploration and questioning of the visual images that humanity has created in its attempt to express faith. Some of those images, such as the fish used by early Christians, were created as clandestine symbols to be used by persecuted members of a cult to recognize each other. |

|

Other images were created as pure acts of adoration, such as the image of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary, the Santa Muerte of the Maya Indians, the representations of their Gods by the Greeks, the Romans, the Egyptians, the Assyro-Babylonians, the Celts, the Norse, the Finno-Ugrians, the Africans, and all peoples of the Earth from Paleolithic times to the present. There is no race, no tribe, no group of humans that has not produced art as an act of adoration, and as an expression of faith. |

The thread that both unites and distinguishes these images is the coloration produced by culture. Ancient writings from different societies and civilizations reveal Gods and Goddesses that existed across many cultures, identifiable as the same by shared characteristics, shared powers for intervention in human affairs, and shared taboos. Yet these obviously identical Gods and Goddesses appear very different in images made of them in different cultures, because of the influence of cultural perceptions of beauty and power. |

Nonetheless, even in these varied manifestations of the same deity, the same divine symbols appear and reappear, and continue today in modern images in churches and temples of the twenty-first century. Ancient crosscultural variations and repetitions of symbology are clearly visible in the icons and orthodoxy of contemporary world religions. |

|

Just as ancient peoples did, we interpret our Gods and Saints to conform to our own cultural standards; and although we thusly alter them, we continue to use the symbols that have survived for millennia. Nonetheless, if this is pointed out, cries of blasphemy and profanity arise, and connections and common threads are denied, thus denying the continuity which, if accepted, could be an abundant source of self knowledge and understanding. |

|

We accept crosscultural fusions of iconographic imagery and symbols in societies other than our own; yet when it is pointed out that our own religious icons have the same fusions and symbols, we rail against the heresy. My work focuses on these iconographic fusions and on the unbroken continuum of symbolic representations that have existed throughout our history. Of course, my own beliefs and questionings color the work, and so I become a part of the very phenomenon that so fascinates me. |

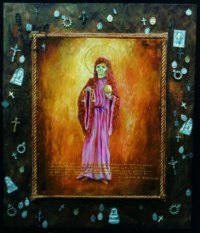

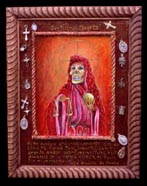

For example, I have painted several depictions of "Santa Muerte," or "Saint Death," a ubiquitous icon among contemporary Maya in southern Mexico, available on estampas, small paper "holy cards," in front of churches, cathedrals, or in village squares, complete with a prayer to Saint Death on the reverse side. I believe this image to be the blending of the ancient Mayan God of Death, Quetzalcoatl, with the Catholic notion of Sainthood brought by early missionaries. When the missionaries would not allow the Maya to keep their traditional Gods, the Maya simply converted Quetzalcoatl into a Saint. The Church today silently overlooks this conversion, as did the missionaries, and the Maya kneel at Mass and pray to Santa Muerte to give them a peaceful and holy death. |

|

|

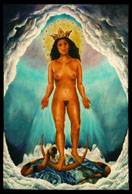

While we accept such an "exotic" conversion, we have difficulty viewing our own icons as having undergone similar cultural overlays of piety. In traditional Catholic iconography, the image of the Virgin Mary in Immaculate Conception is based on a painting by the 16th century Spanish artist Murillo. Mary is shown standing on a crescent moon, over the Earth, with her halo of twelve stars, the serpent at her feet, poised to crush its head, and rays of grace coming out of her hands. |

Although it is commonly agreed that the twelve stars are taken from St. John's vision in the Apocalypse, it is also agreed among theologians that there is no source for the crescent moon upon which Mary stands other than ancient concepts equating the moon with many Goddesses through the millennia, including the Virgin Goddess Diana, and the great Goddess Isis, whose golden horns are synonomous with the crescent moon, and whose temples portrayed her riding in her moon-boat. |

|

|

Isis was worshiped throughout the ancient Greco-Roman-Egyptian world, from Alexandria to Britain, through the Asturian mountains and the valleys of the Danube, to the ends of the Sahara. Her worship flourished in Rome until it was syncretically absorbed by Christian veneration of Mary, which incorporated extensive identifications with Isis, including the journey with her child into Egypt. Our familiar depictions of Madonna and Child have their foundation in similar iconographic traditions of Isis and her son Horus. |

Mary's victory over the serpent seemingly has its origin in the curse of Yahweh, described in Genesis, as punishment for the snake for enticing the woman to eat from the forbidden tree. Notwithstanding the original Hebrew writings which say, "He will bruise your head," most modern Biblical translations come from Latin translations which say, "She will crush your head." Nonetheless, Genesis was the last book of the Pentateuch to be written, and was not formalized until about the 6th century B.C., during the Babylonian exile. |

Even slight delving into ancient religions reveals the serpent to be the most venerated and worshiped of animals. It was worshipped among the Hebrew tribes long before Yahweh arose as the one God; the Hebrew priestly clan, the Levites, were sons of Leviathan, the great serpent, the wriggly one. The Hebrew word for the divine serpent was Seraph, which is now colored to mean, "Angel." |

|

Babylonian icons depicted the serpent attending the Goddess and offering the food of immortality to her people. For the writers of Genesis, the serpent epitomized all their rival religions. It was only natural that they would attempt to strike it from its lofty place and make it culpable for all of the woes and tribulations of their people. |

|

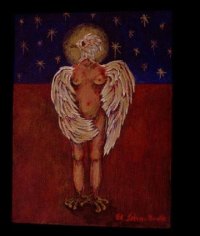

In my painting, "Immaculate Conception," my questioning of the traditional icon resulted in the serpent appearing as friend and protector to Mary. I did not portray Mary as the fragile, blonde, blue-or green-eyed slip of a girl seen in churches the world over. Could Mary really have looked so much like a contemporary, Western Catholic school girl? I painted her as the Semitic woman she was, swarthy, with dark, kinky hair, robust and sturdy, capable of making the three-day trek on foot and donkey from Nazareth to Bethlehem during the final days of her pregnancy. |

The moon reflects the Horns of Isis. Mary is painted nude, as Genesis reveals that those who are without sin are not conscious of nakedness.....Adam and Eve clothed themselves only after the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge allowed them to see that they were uncovered. It follows that true depictions of Mary as Immaculata must, according to the Bible, and if we are not to color them with our own cultural perceptions, show her unclothed. Far from profane, my intention was to make this my highest possible tribute to her. |

|

Inconsistencies abound in our most profound and intimate sacred beliefs. Cultural stereotypes permeate those beliefs. My work is a search for personal faith, and an expression of faith in our ability to overcome these inconsistencies and stereotypes to reach a fuller understanding of the consistency we do have with our own ancient history and belief systems, thus better to understand ourselves, and to achieve the calm and peace that understanding always brings. |

|